In mid-April 2021, I began receiving reports from sources in China and the United States that certain regions in China had begun to experience ongoing power disruptions at their warehouses and manufacturing facilities. Most notable of these was in south China’s Guangdong megaregion, where in June operations at the Taishan Nuclear Power Plant had become disrupted by a small number of faulty claddings for the fuel rods, ultimately forcing state-owned General Nuclear Power Group to shut down Unit 1 (there are two units) for maintenance and repair. Concurrently, available power imported to the Guangdong region from Yunnan province’s considerable hydroelectric capacity was reduced due to drier-than-expected weather throughout the spring.

Taken together, some estimates are that total power available to the region fell by as much as 15% by June. In response, officials began quietly rationing power to factories, cutting business operation days by 1 or 2 days depending on the facilities’ power requirements.

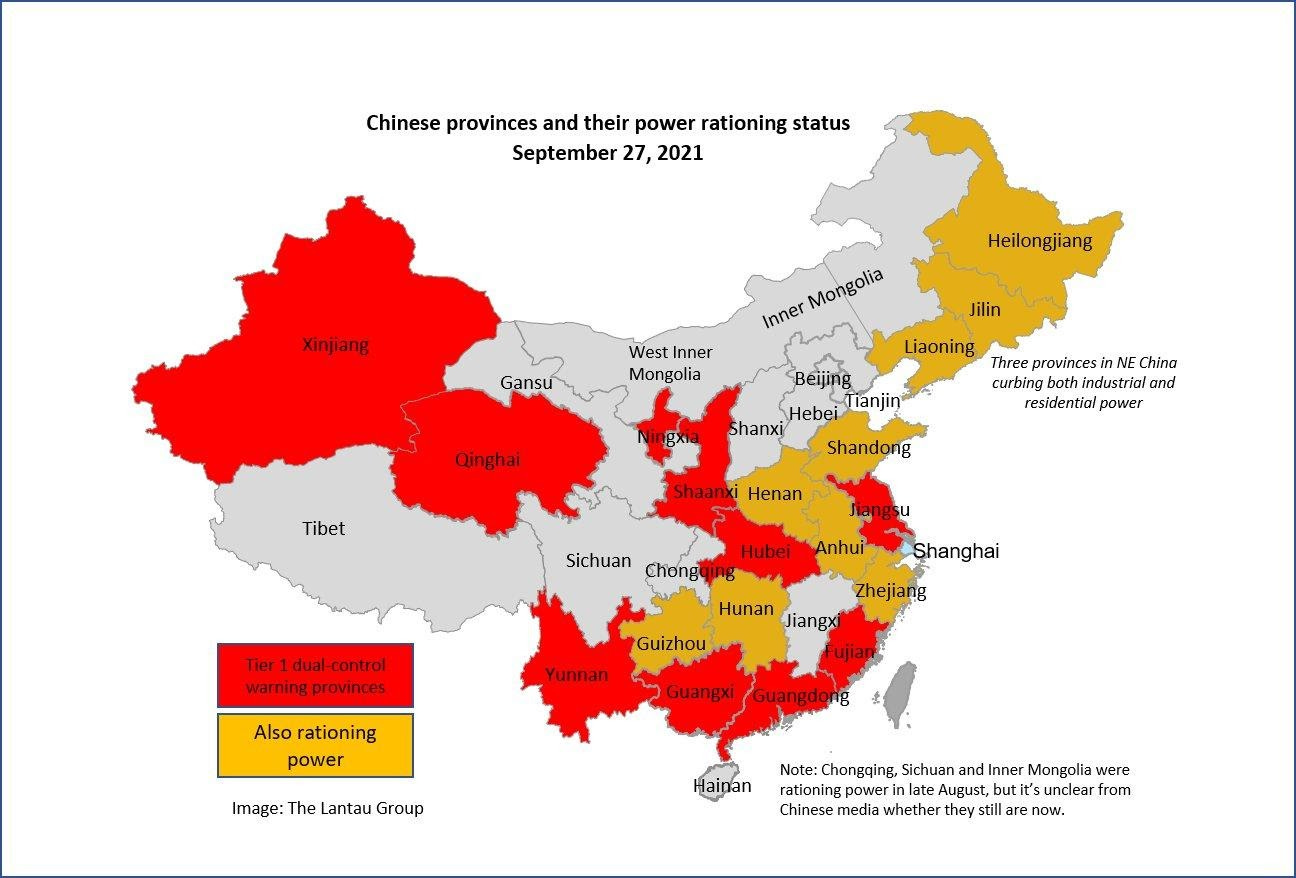

In recent weeks, however, officials have begun a much more aggressive rationing program (Figure 1), with factories in much of Guangdong now seeing only 1-2 days per week of power use allowed. Similar situations are reportedly occurring in Jiangsu, Hubei, and Fujian provinces, all major manufacturing regions. As just one example, one of my US-based import customers has reported that a key supplier in Jiangsu is down to a single day per week of power availability. Limited-but-expanded power rationing is also occurring in Zhejiang, Shandong, Liaoning, and other important heavy industrial, chemical, and energy-product hubs.

Figure 1 - Chinese Province Power Rationing Regime - Courtesy of The Lantau Group

The primary causes of power disruptions are the aforementioned reduced availability of hydroelectric power in much of southern China, as well as limited supplies of coal due to the ongoing China/Australia trade dispute. The latter cause is expected to be more sustained in impact, as the year-long embargo by China on Australian thermal coal has depleted China’s strategic reserves and caused commercial and residential prices to rapidly spike. China imports about 10% of its annual thermal coal needs; of this, Australia was close to 70% of the total prior to the mid-2020 embargo. It is expected that China will be forced to drop the embargo ahead of the fourth quarter, but this is not certain. Reopening its markets to Australian coal imports would be an important stabilizing step for China’s manufacturing base, but would nonetheless take weeks or even months to ramp back up to normal output.

If China does not capitulate on the importation of Australian coal and cannot close the gap with imports from Brazil, South Africa, and the US, the southern region will continue to see constrained power availability, reducing export volumes especially from Shenzhen’s ports, Hong Kong, and Xiamen, as well as Tianjin, Dalian, and Qingdao in the north. We would expect in this scenario to see these ports be utilized by ocean carriers for more transshipments out of Southeast Asia or central China, while export-focused capacity shifts to Ningbo and Shanghai, as well as alleviating significant congestion pressure at Kaohsiung and Busan. Freight rates are anticipated by some maritime industry players to soften somewhat, though a bullish case for barely-reduced rates could be made that a very large backlog of existing cargo and ongoing delays at US and European ports will keep volumes at a high level through Lunar New Year at least, with a strong likelihood of continuing through the ILWU negotiations.

Looking at 2022, any significant level of ongoing power disruptions will begin to cause fractures in China’s economy, particularly in the finance and heavy manufacturing sectors as well as within the population. Such fissures have in the past led to increased belligerence by China against neighboring and regional countries, which could have unexpected disruptive effects on maritime and air traffic in the Far East. With regard to which sectors of the economic base will receive favored treatment for any surplus power, heavy manufacturing (auto, shipbuilding, infrastructure), high technology, energy (renewable and traditional), petrochemicals, medical, and metal processing will likely be protected first. These are considered critical industries in China due to the PLA’s direct investments into these sectors (as well as the in-kind benefits to China’s military industrial complex), with industries such as homegoods, consumer electronics, and garments receiving the least support. This will in particular impact retailers in the US and Europe who are already falling short on inventory, and were hoping for a strong late-year push to close the earnings year on a high note.

More broadly, it should be expected that the continuity and consistency that China-based supply chains have historically enjoyed will be diminished in the short- to intermediate-term. Fortis expects that Xi will tip China’s dual-circulation economic strategy in favor of protecting domestic consumers, particularly to offset the political instability introduced by energy and food price increases. We can also reasonably expect to see internal enemies of the CCP and PLA be targeted for power rationing, or even villainized as over-users of precious energy resources at the expense of the civilian population. In closing, the energy disruptions in China are but one more canary in the coal mine indicating accelerating catastrophic failure cascades, further consolidation of internal power by Xi and the CCP, and an ongoing bifurcation of geopolitical spheres between China and the US.

Dum spiro spero,

RK

According to @baldingsworld coal supply is not the issue. Rather it is that power generators are required to sell power at a fixed price per kwh while buying coal at the spot (escalating) price causing losses on every kw produced. There was a headline Friday that the generators were being allowed to raise rates. So we should see this conflict begin to abate.