[Author’s Note: this is the first of two articles focusing on the factors impacting China’s food security and associated geopolitical maneuvers.]

“The thoughts of the Chairman [Mao] are always correct. If we encounter any problems, any difficulty, it is because we have not followed the instructions of the Chairman closely enough, because we have ignored or circumscribed the Chairman’s advice.”

Lin Biao, January 1962

“When there is not enough to eat, people starve to death. It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill.”

Mao Zedong, 1959

”It was the greatest contribution towards the whole of human race, made by China, is to prevent its 1.3 billion people from hunger.”

Xi Jinping, 2009

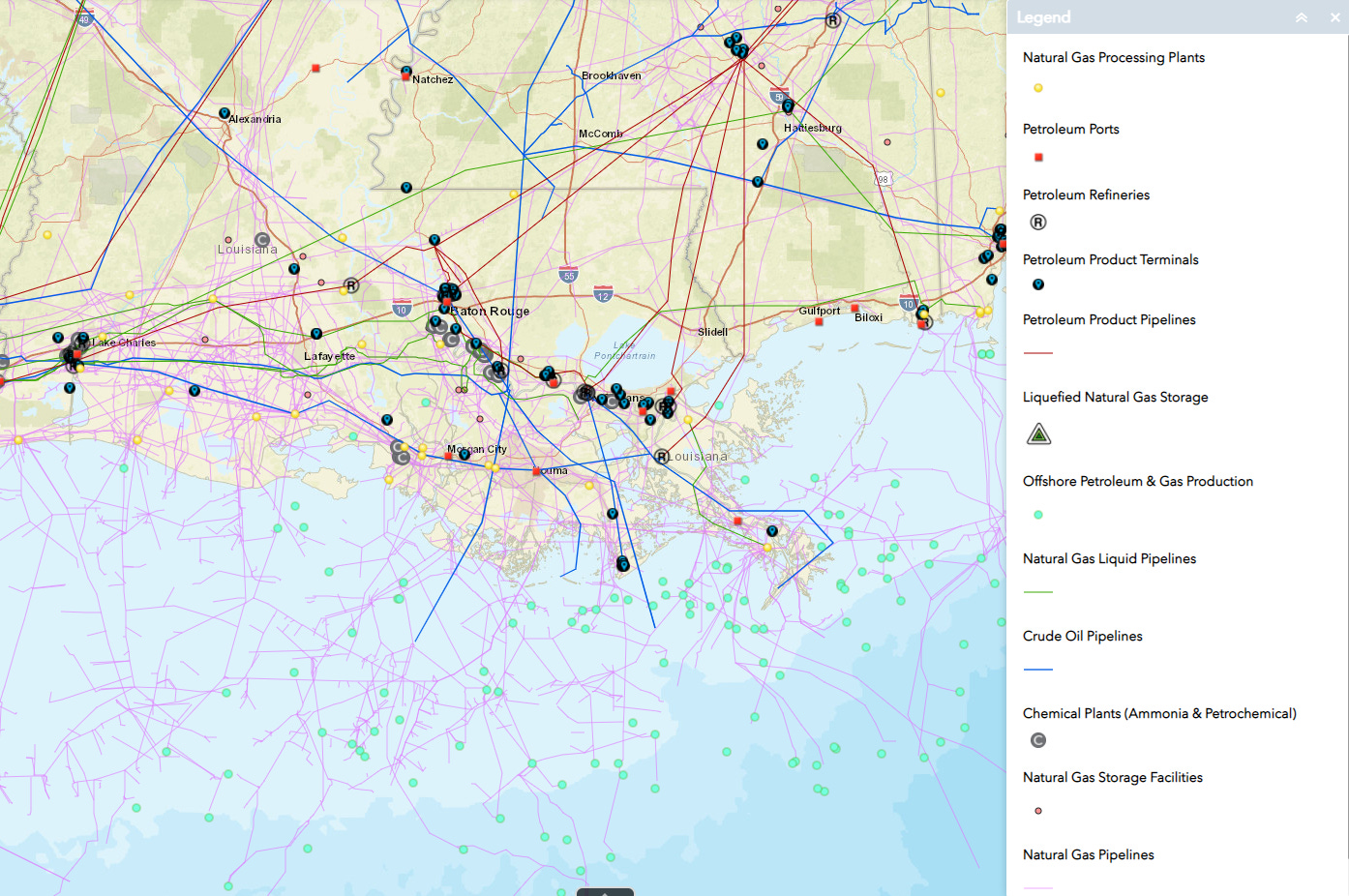

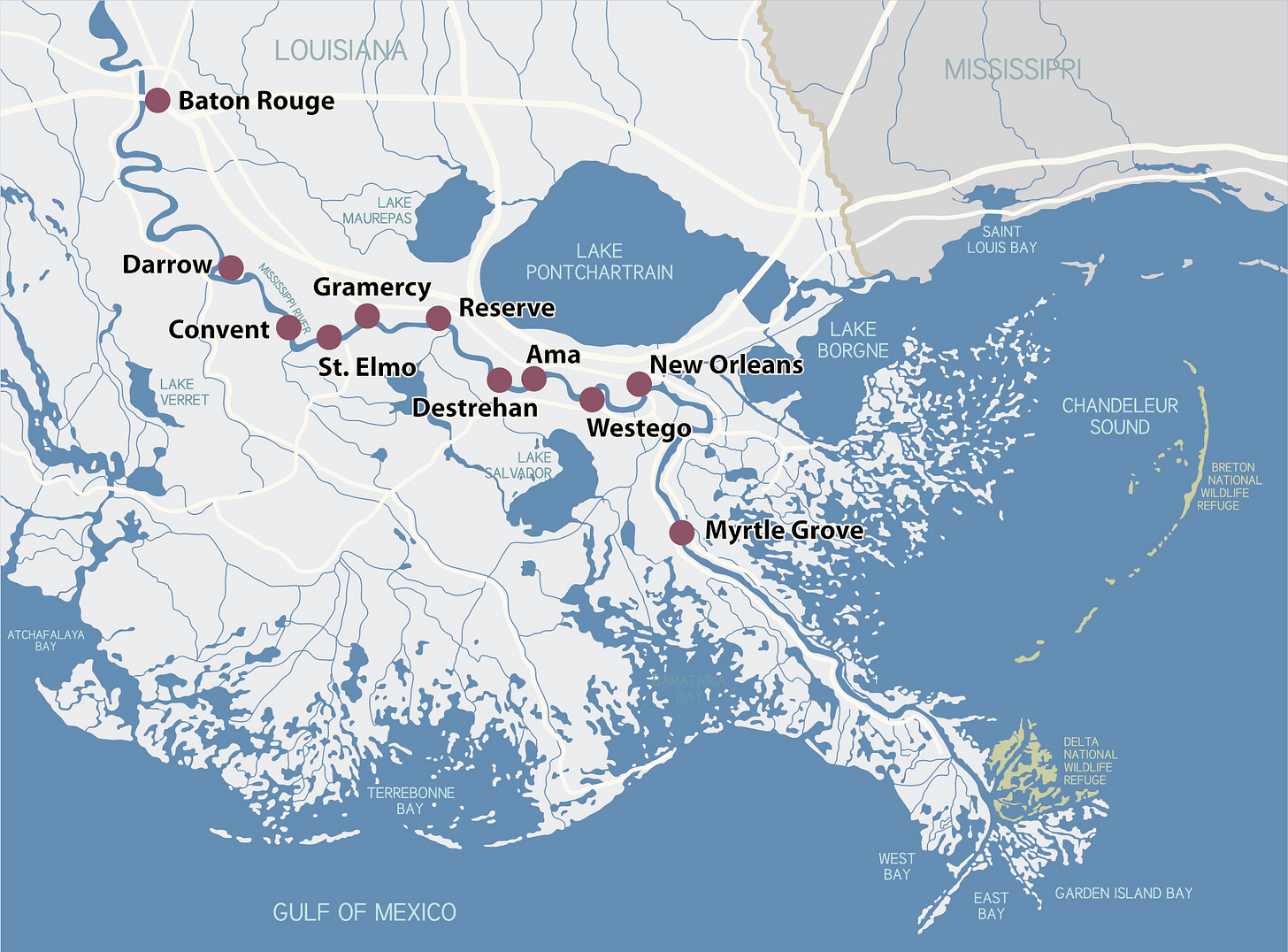

When Hurricane Ida made landfall on Sunday, 29 August at southern Louisiana as a violent and dangerous Category Four storm, there were reasonable fears of total devastation of the petrochemical infrastructure in the region. Given its location astride the Mississippi River delta river transportation hub (Image 1), and the region’s vast hydrocarbon supply chain activities (Image 2), the seaboard of Louisiana has become an indispensible energy resource for the United States.

(Image 1) Inland Waterway Map - Courtesy of Port of South Louisana

(Image 2) Selected Hydrocarbon Infrastructure - Courtesy of FracTracker Alliance

Most of the attention post-Ida has thus focused on quantifying damage to the region’s energy industry, especially as Ida made landfall directly on top of Port Fourchon, the gateway hub for servicing the offshore drilling industry in the Gulf of Mexico. With the port now in absolute disarray, the offshore rigs are at a production standstill for up to several weeks, leaving refiners with reduced inventory to process into fuels and chemicals. Understandably, this makes policy-makers, refiners, and consumers extremely nervous about a spike in prices for a whole range of petrochemical products ranging from gasoline to polypropylene to resins.

Overlooked in much of the mainstream analysis of Ida’s impact, however, is the critical role southern Louisiana plays in the United States’ agriculture industry. The various terminals (Image 3) in the lower Mississippi River (the 250-mile stretch of river from Baton Rouge to the Gulf of Mexico) are responsible for some 59% of US corn exports and 60% of US soybean exports, as of 2020.

(Image 3) Lower Mississippi River ports - Courtesy of LSU AgCenter

Further, volumes of corn exports via the region’s terminals skyrocketed in the most recent marketing year (1 Sep 2020 - 31 Aug 2021), with a 42% year over year increase for the first six months of 2021 versus 2020. We can adjust for the demand drag of those early months of the COVID-19 pandemic by comparing previous years:

Q1/Q2 2021 vs. 2019: 102% increase

Q1/Q2 2021 vs. 2018: 48% increase

Q1/Q2 2021 vs. 2017: 40% increase

Data via Port of South Louisiana

The story is a bit different for soybeans, however. Exports fell by 4% from Q1/Q2 2020, with a similar decrease versus previous years.

Q1/Q2 2021 vs. 2019: 9% decrease

Q1/Q2 2021 vs. 2018: 5% decrease

Q1/Q2 2021 vs. 2017: 7% decrease

Data via Port of South Louisiana

Some of the difference can be accounted for by the fact that the US exports a larger percentage of its soybeans via ocean container from the heartland than corn. This is due to corn requiring 40-foot containers, while soybeans can use 20- or 40-foot units, a feature of soybeans being able to pack more densely than corn, making more efficient use of the cargo weight limits per container (i.e. more bushels in less space). Further, many of the US’ non-China soybean customers prefer containers over bulk due to being able to purchase in smaller quantities, stabilizing their import supply chains.

However, the pandemic-driven disruption to supply chains has had a major knock-on effect for containerized grain and oilseed exporters: lack of containers in the interior, and chassis to move the containers on the road. The extreme volume increase of imports - and resulting congestion - in such a relatively short time has caused ocean carriers to begin restricting container flow to major rail-served interior markets. This has particularly choked container availability in Chicago, from where a significant portion of the US’ containerized agri exports originate.

Taken together, the hopes of farmers, exporters, and buyers were pinned on the ports and terminals of South Louisiana being able to pick up the slack for export capacity as the US enters harvest. Unfortunately, this will not be the case until at least October or even November. Both of Cargill’s terminals in the region impacted by Ida are offline, with the 6-million bushel capacity facility in Reserve suffering extreme damage that could take months to repair. CHS Inc.’s primary export terminal at Myrtle Grove also suffered damage to the power lines that serve the facility, along with water intrusion to the grain handling equipment. Similarly, Archer Daniels Midland, Zen-Noh, LDC, and Bunge have reported power interruptions and varying degrees of damage at their regional facilities. Lastly, navigation on the lower Mississippi River continues to be slowed by flotsam and power outages.

Now, what does this have to do with China and the immediate future of the Transpacific power struggle?

In short - China is desperately short of crucial grains and oilseeds needed for domestic human and animal consumption. Understand, food security is not an unknown issue in China. So too is it widely known that CCP media organs and official ministries routinely lie about a range of food-related issues, from grain and oilseed production to hog population and slaughter figures. The CCP even went so far as to engineer the collapse and takeover of Swiss agriculture and chemical conglomerate Syngenta several years ago to short-path China’s rise to being a tier one agriculture research powerhouse alongside the United States, Japan, and the European Union.

The immediate causes of China’s food security woes are twofold:

An ongoing, multi-year outbreak of African Swine Fever

Two consecutive years of reduced grain and oilseed production due to widespread catastrophic flooding

Despite China’s rosy claims about its 2020 production, its year-long buying binge for available global inventory of grains and oilseeds indicates significant flooding-related production woes in several major agricultural reasons in the Yangtze River and Amur River basins. 2021 is shaping up to be potentially as bad. Notably, the critical crop-producing province of Heilongjiang (16% of China’s total corn production, and 40% for soybeans) is showing significant excess moisture stress during the critical corn development stages between pre-tassel and silking, with excess moisture also being a major factor in yield drag for soybeans during seed-fill. The general time period for both crops to reach these reproductive stages are July through end of August.

Closely related to the trade indicators for grain production, import, and consumption is the issue of animal feed. Contra its massive buying spree throughout 2020 and early 2021, China’s imports have now slowed a touch, ostensibly due to hog growers feeding cheaper available wheat in lieu of pricier soybeans, corn, and their various co-products. But as indicated by the article from The Economist linked above, it’s more likely a signal that pork production is falling dramatically due to the re-emergence of African Swine Fever. Note that at its peak in 2018-2019, ASF was estimated to have forced China to cull at least 50% of its hog population and store the infected carcasses in freezers all over the country.

Bringing it full circle to the devastation to US agri export capacity wrought by Hurricane Ida, there is now an imbalance of supply and demand such as we have not seen in a long time. Whereas before, China was able to make up shortfalls in domestic production by sourcing from the US, Brazil, Ukraine, Europe and others, that optionality is gone. The US’ primary grain and oilseed export hub of southern Louisiana lies in disrepair, with US yields expected to be basically at trendline, with unknown impact to grain and oilseed quality due to drought stress in some regions. Early indicators of crop quality are a bit worrisome, with the most recent USDA Crop Progress Report released on 30 Aug 2021 showing corn conditions at 60% Good/Excellent (62% last year) and soybeans at 55% Good/Excellent (66% last year). What is available to China will likely be of reduced quality and more expensive to transport from alternate US origins.

The news is not much better in China’s traditional breadbasket. Brazil’s safrinha (second corn crop) has historically been the export-maker for the country, with China a major buyer each year. However, due to disastrous planting conditions and weather challenges, production is expected be 20% lower versus last year, dragging corn exports down by 33% year-over-year. Though Brazil’s soybean production is about 9% higher than 2020, availability of bulk cargo vessels is constrained, with global dry bulk freight rates roughly 40% higher than the previous five-year peak (pre-2021) set in Q3 of 2019.

It appears Ukraine and Russia will have to pick up the slack from the grains side, as both countries are projecting 29% and 19% production increases over 2020, respectively. In terms of overall cost on an “FOB” basis (Free On Board, a term of sale that reflects cost to purchase the product and transport it from an origin port), Argentina is still the most competitive source of corn for China, but only produces about half the volume as Brazil. Oilseed (especially soybeans) availability looks stable worldwide with no significant production issues noted so far, but logistics constraints impact the trade as much as it does for corn, as well as enduring worries about weather challenges to crop quality (if not quantity).

An understanding on major grain trade factors is important to understanding the rest of the series of articles to come on this, as a significant portion of Chinese demand and consumption for corn and soybeans is tied to animal feed. A fantastic global overview of grain and oilseed trade flows prepared by Rabobank showcases just how much of a demand bull China is for these commodities (Image 4 - click here for a zoomable version).

(Image 4) World Grains and Oilseeds Map - Courtesy of Rabobank

The simple reason is that China consumes enormous quantities of animal protein products. Though it is middle of the pack in annual per-capita consumption at 49.3 kg (compared to the US at 100.7 kg), the overall appetites of 1.41 billion people generates demand for more than 90 million tons of pork, poultry, and beef products. The US, with its population being roughly a quarter of China’s, uses around 44 million tons of the same proteins per year. Further, China is far and away the global leader in aquaculture production (“farmed” marine protein, vice “capture” fisheries in the world’s oceans) at 68.4 million tons produced annually, while the US checks in at 490,000 tons. Similarly, China’s capture fishing activities utilizing its massive commercial fishing fleet is reported to generate another 14.4 million tons of protein, while US fishing is comparatively much smaller at 5.35 million tons. And yet with all of that effort, China cannot catch a break as Brazil has been forced to temporarily suspend all beef exports to China over an outbreak of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or “mad cow disease”), cutting off China’s source of around 71,000 tons per month of beef.

Adding all of this up, we see that China has an astoundingly large quantity of protein to produce and import for its population. Taken together with the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s fears of social upheaval due to food insecurity (and the stain upon the party from the Great Leap Forward), the impetus for much of China’s belligerence in global fishing and crackdowns on commodities trading become clear. Broadly speaking, the confluence of supply side and logistics disruptions has formed into a perfect storm, where China cannot as readily meet its current food demand through production, trade, acquiring foreign food manufacturers, and even illegal activities such as illicit fishing.

Which begs the question - what can we extrapolate from this information to better-predict China’s behaviors in the coming months, the US’ responses, and the impact to global stability?

The next newsletter will dive into that question.

Thank you for reading.

Dum spiro spero,

-RK

I would add item 3 on your list of pork production problems is the lack of a free market price signal mechanism. Read an article recently that talked about over production causing pork prices to crash internally and many hog producers were not filling spots on their feeding floors but were being encouraged to do so by local authorities. Now with ASF supposedly reappearing it is causing a major shortfall of pigs to slaughter. However, they don't seem to be coming to the US looking for pork imports so I am wondering if they may have overplayed their hand. Another recent article stated a 5% drop in pig numbers but a 14% drop in pork tonnage-indicating lower slaughter weights indicating the pigs are being pulled forward. Also, I was taught that FOB was at a point-either origin or destination so it may or may not include freight.